Unrolling the roll

Unrolling the roll

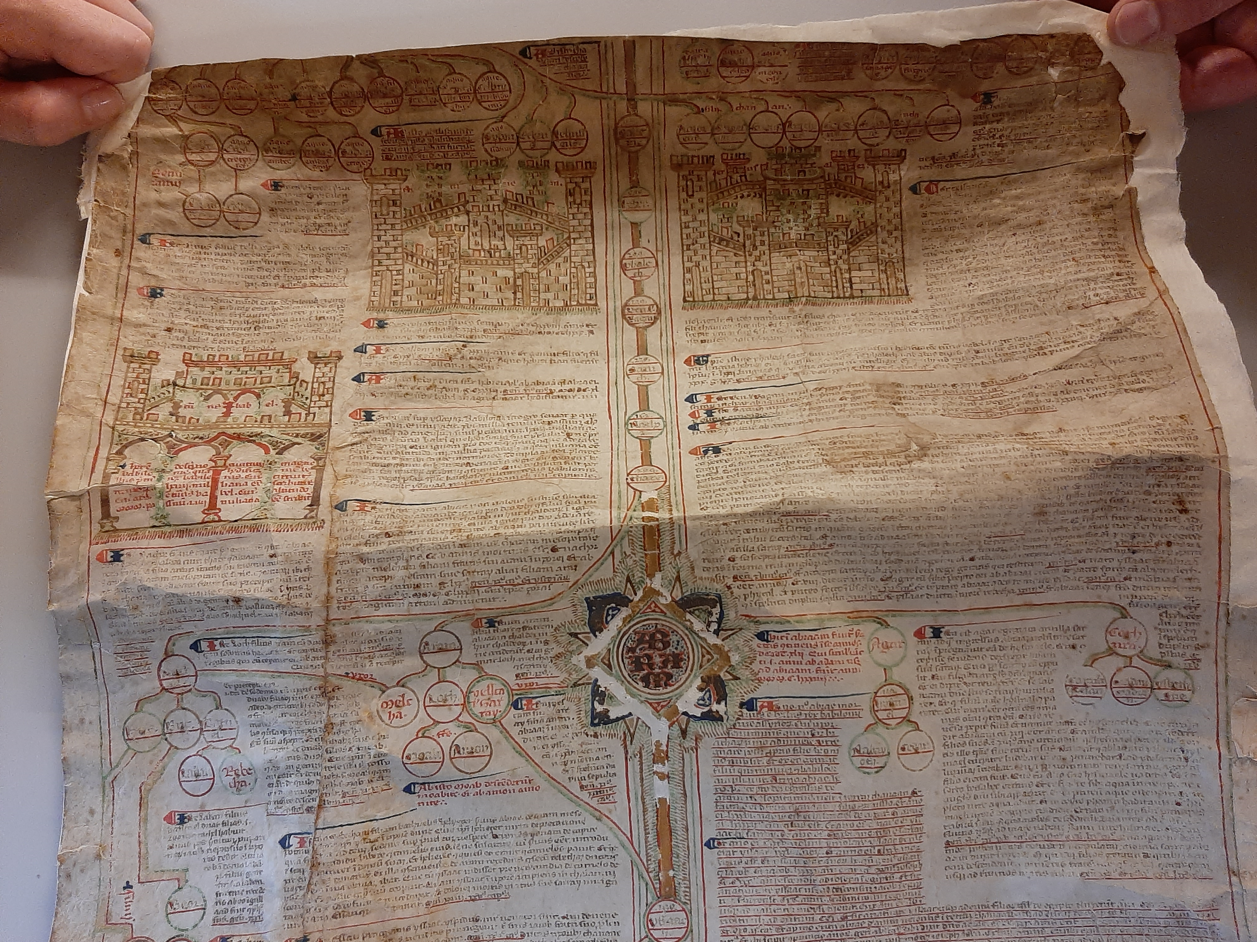

Part of the Special Collections of the Athenaeumbibliotheek is a 14th-century parchment roll containing a world chronicle (Deventer, AB, 11 J KL). Composed of nine membranes (sheets) glued together, the roll is 4.3 metres long and almost half a metre wide. At one time the roll was probably longer, but the head seems to be missing. The roll contains a history of the world, oriented on the Bible. In its present form it begins with the story of the flood. Medallions scattered across the centre and along both sides of the roll give the names of biblical figures and rulers from world history. The medallions provide a visual anchor for stories about events that took place in their day and age. The stories, recorded around the medallions, feature colourful drawings in red, green, blue and gold. The line of medallions showing a genealogy of Christ continues via Peter with a list of popes, while the line of Roman emperors ends in a list of emperors of the Holy Roman Empire.

Deventer, Athenaeumbibliotheek, 11 J KL, roll (detail). Photo: Irene van Renswoude

Suzan Folkerts (curator), Suzan Boreel, Carmen Burgio, Mariken Teeuwen, Julia Knol, Emma Joppe. Foto: Irene van Renswoude

How was a roll like this actually used? A roll made of parchment is stiff and not easy to handle. A common theory is that illustrated rolls were brought out on special days and unrolled on a long table. A select company would then walk along the table to read the text and look at the illustrations. We tried this out during a visit to the Athenaeumbibliotheek with a group of trainees from the eCodicesNL project. Curator Suzan Folkerts gave us permission to unroll the roll on a long table. During this experiment, we found that the written text is actually too small to read when standing around the table. Even the names in the medallions are difficult to read from a distance. A more probable scenario is that someone who knew the contents of the roll by heart retold the stories while guests around the table looked at the illustrations.

Not much research has been done on the use of rolls during the Middle Ages. More research would be most welcome. What should also be considered further is how best to digitise a roll. In this portal, which includes images the Athenaeumbibliotheek has commissioned from Picturae, the roll is presented in a single image. The possibilities for scrolling through the roll and zooming in are therefore limited. Other libraries and institutions sometimes choose to photograph a scroll membrane by membrane. Although this procedure enhances the quality of the images, the presentation of separate pages on a screen creates the optical illusion of a codex rather than a roll. Going from one image to the next, instead of ‘scrolling’ down the roll, obfuscates a clear understanding of the roll as a physical object. A possible solution would be to create a video of the roll (see Kate Rudy, ‘Video killed the photo star’) to complement the presentation of images of individual membranes. While individual images would allow zooming in, the video would capture the physical characteristics of the roll and show how the roll ‘behaves’ when handled. As we expand the portal in the coming years, we want to explore new ways of digitising not only complex objects such as rolls, but also ‘average’ codices.

Kathryn Rudy, Video killed the photo star: Digital photography and the challenges of folded and rolled manuscripts. 1 oktober 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LyoNARyvFZA