The oldest manuscript in Tresoar

Leeuwarden, Tresoar, PBF 55 hs: Attic Nights

The oldest manuscript in the Tresoar collection is a manuscript in which a copy of the text Attic Nights (Noctes Atticae) by Aulus Gellius (c 123- c 180 CE) has survived. Apart from being one of the oldest dated manuscripts in the Netherlands – more about this later –, there are several reasons to give this manuscript special attention, even if it is not decorated with gold and miniatures.

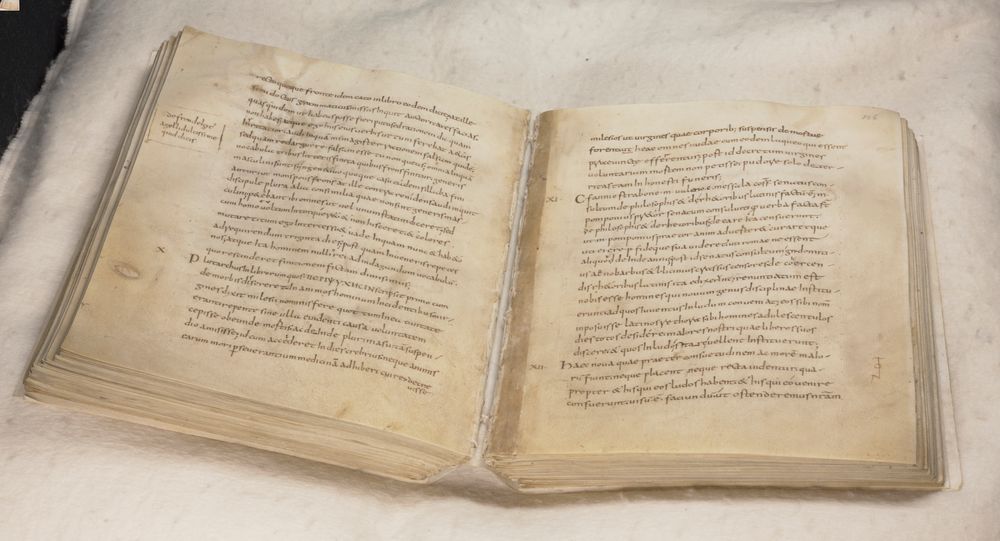

Leeuwarden, Tresoar, PBF 55 hs (Open view)

Indeed, the book appears, as the manuscript scholar G.I. Lieftinck from Leiden University already argued in 1955, in two letters from the ninth century. The letter writer is Lupus of Ferrières (c. 805- c. 862), a learned monk who was sent from his monastery in Ferrières to Fulda to study with abbot Hrabanus Maurus (780-856). Hrabanus pursued an active policy to collect ancient texts for the Fulda library. Lupus was also committed to this: in 829 or 830, he wrote a letter to Einhard, Charlemagne’s famous and learned former chaplain, asking if he could borrow some of his books from Seligenstadt for a while to have them transcribed for the library: he mentions Cicero’s treatise on rhetoric (“Tulli de rhetorica liber”) and Aulus Gellius’ Attic nights (“Agelii noctium Atticarum”). In 836, Lupus writes another letter to Einhard, this time apologising for not yet being able to return the borrowed copy of Aulus Gellius, because Hrabanus has taken it away from him:

“Agellium misissem, nisi rursus illum abbas [read: Hrabanus] retinuisset, questus necum sibi eum esse descriptum. Scripturum se tamen vobis dixit quod praefatum librum vi mihi extoserit. Verum et illum et omnes caeteros, quibus vestra liberalitate fruor, per me, se Deus vult, vobis ipse restituet.”

“I would have sent you the Aulus Gellius, if the abbot [read: Hrabanus] had not kept it, complaining that a copy had not yet been made for him. He will write to you, however, he says, and tell you that he forcibly took this book away from me. But if God so wills, I shall return this book myself, as well as all the rest which I enjoy because of your generosity.”

On the basis of these letters, Lieftinck argued that the manuscript now on display in the Tresoar collection is the one written down at Fulda, and this must have happened around the year 836.

Looking at the manuscript itself, we see a number of characteristics that support this. Firstly, the format of the manuscript is remarkable: it is almost square, a characteristic of books from the first half of the ninth century. (Later, the rectangular format becomes more common.) Secondly, we see a mix of types of script consistent with what might be expected at Fulda: the monastery housed both writers educated in the Anglo-Saxon world and on the continent, and in the book we see both insular writing and the continental Carolingian type. On f. 66r, a transition from one type to the other can be seen in the middle of line 15.

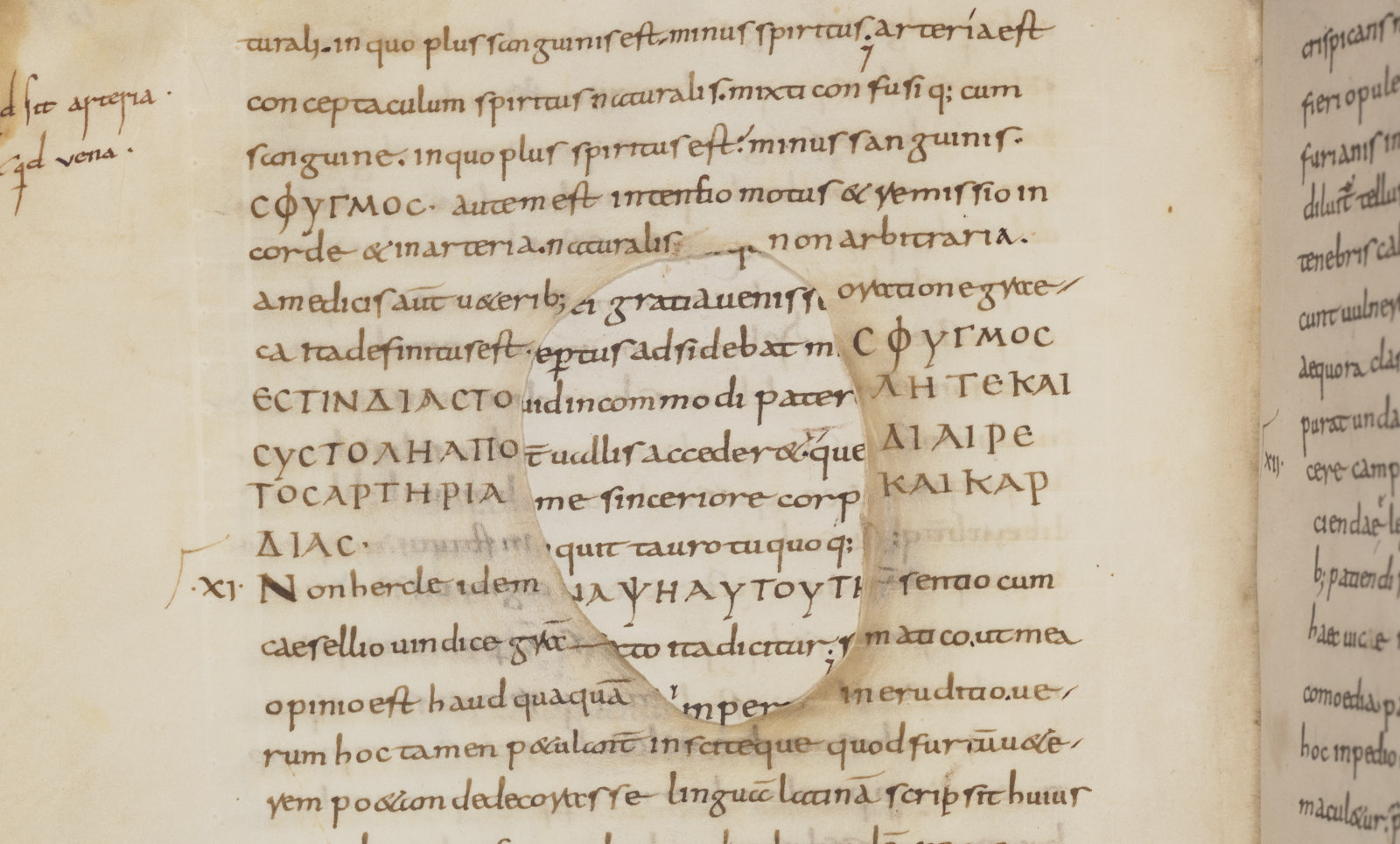

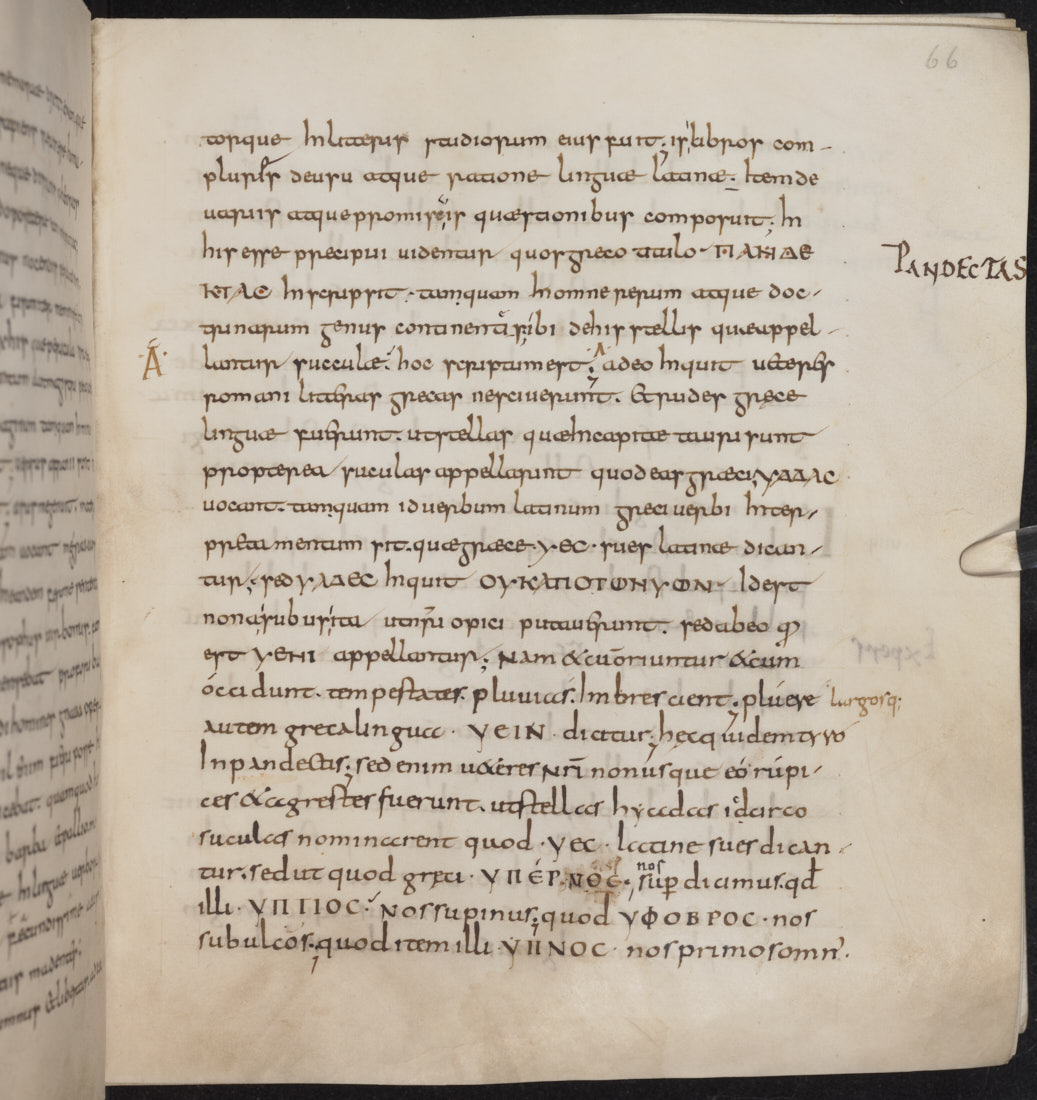

Leeuwarden, Tresoar, PBF 55 hs, f. 66r

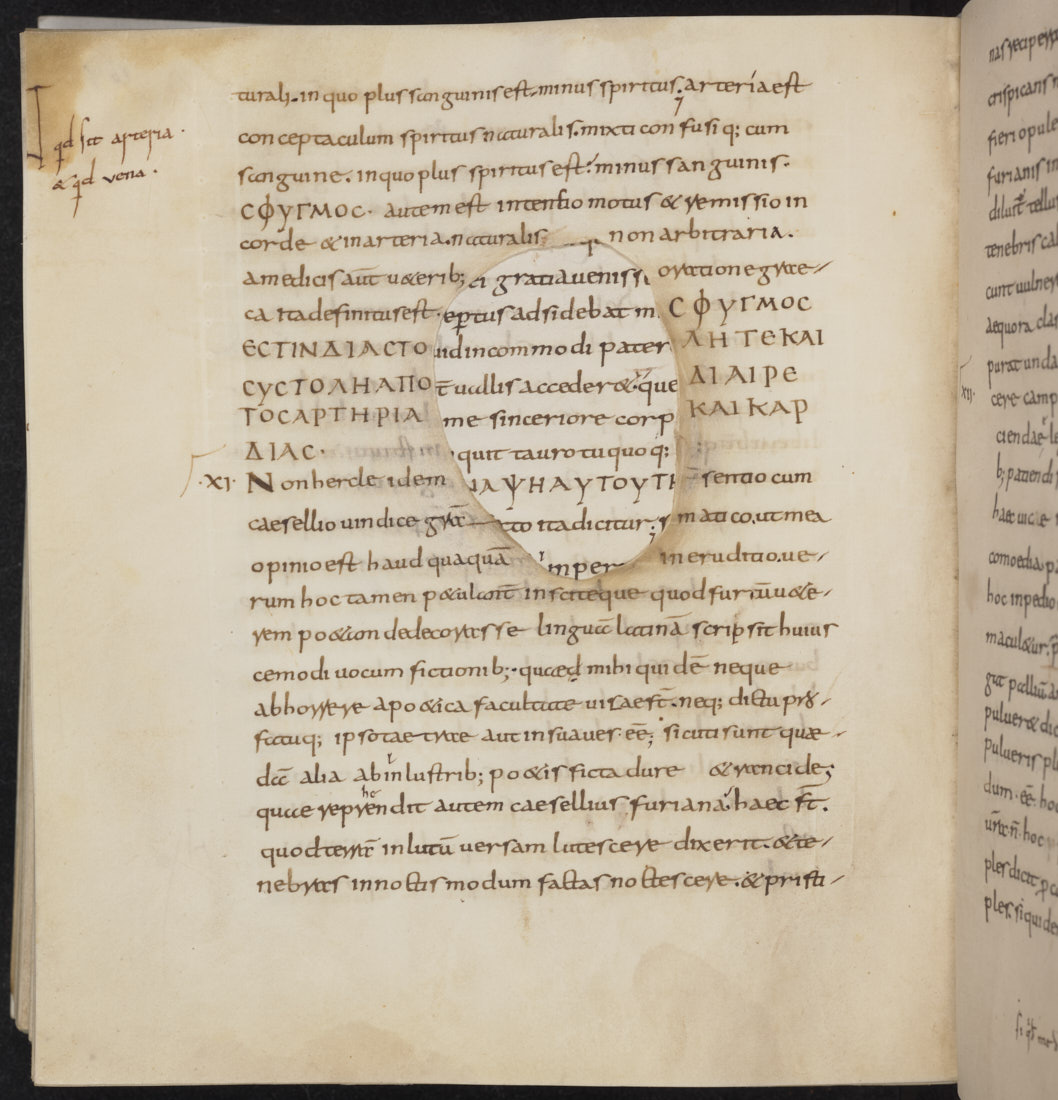

Leeuwarden, Tresoar, PBF 55 hs, f. 164v

Finally, it can be seen that towards the end parchment of increasingly poor quality was used. Finishing the manuscript was a rushed job: the sample book had to be returned to Seligenstadt, where Einhard was impatiently waiting for his book. The text had to be finished even though there was no good parchment available: holes, edges and bad spots can all be found in the last sheets of this book.

Thus, the interplay between Lupus’s letters and the material features of the book itself brings us very close to the historical reality of the distant past: the zeal of Lupus, the severity of Hrabanus and the impatience of Einhard, they are all tangible in this one manuscript.

J.M.M. Hermans, A. Pastoor, Antiquity in Hands. Classical manuscripts in the Provinsjale & Buma Biblioteek fan Fryslân, Leeuwarden 2002, 51-53 and 87-88.

Loup de Ferrières, Correspondance, ed. and transl. L. Levillain (Paris, Vol. I, 1927, vol. II, 1935); English translation in The letters of Lupus of Ferrières. Translated with an Introduction and Notes, by G.W. Regenos (The Hague, 1966), 17.